30 years after Justin Fashanu came out as gay, the spectre of homophobia still hangs over football – but there is hope

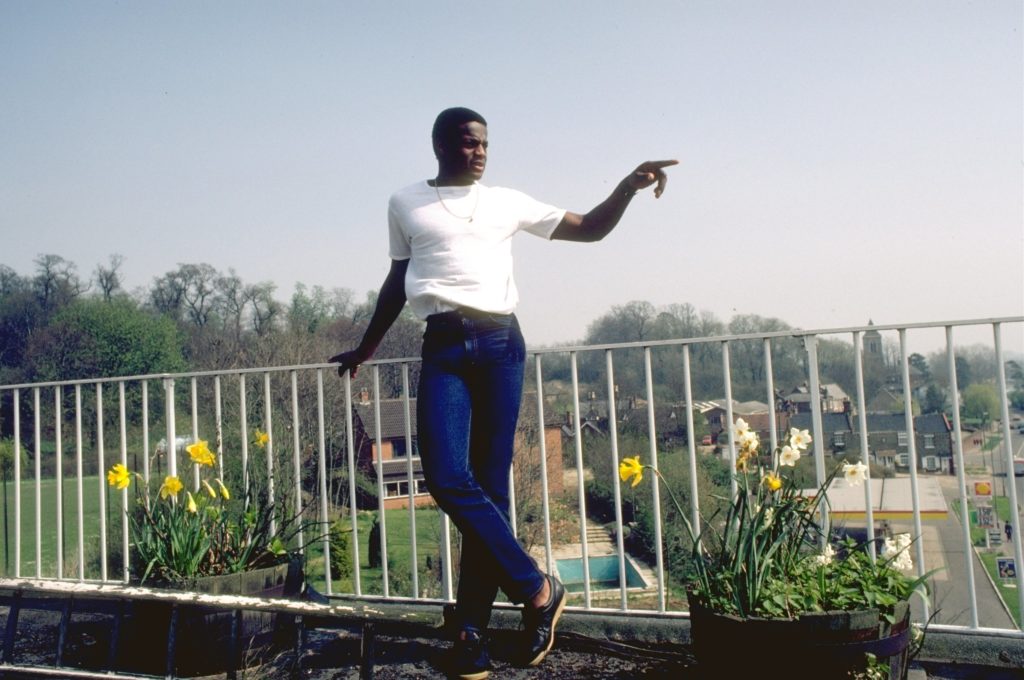

Justin Fashanu of Norwich City. (Allsport UK /Allsport/Getty)

Justin Fashanu came out as gay 30 years ago. While the legacy of his homophobic treatment still hangs over football, there is hope that things are changing for the better.

On October 22, 1990, Fashanu became the first professional footballer to come out publicly. Less than eight years later, with his promising career cut cruelly short by homophobia, he took his own life.

To this day, he is still the UK’s only top-tier male football star to come out as LGBT+ while currently playing. Thomas Beattie, a retired English player who played at professional level in Scotland, Norway, Canada and Singapore, came out in June 2020, while Robbie Rogers, an American player who played for Leeds FC, came out after leaving the club in 2013.

Fashanu’s sexuality was first revealed on the front page of The Sun. The tabloid offered him money for an interview to pre-empt unauthorised revelations that were about to appear in the Sunday People, so, keen to get ahead of the story, Fashanu tried to tell it in his own words.

“£1m Soccer Star: I Am Gay” screamed the headline. Below it were the words “Justin Fashanu confesses”.

Justin Fashanu. (Allsport UK /Allsport/Getty Images)

It was 1990: the UK was in the midst of the AIDS crisis and entering the toxic Section 28 era, where teachers were forbidden from informing children about the existence of LGBT+ people. Fashanu’s private life instantly became a matter of public ridicule.

He was treated like a pariah by everyone around him, facing the double discrimination of racism and homophobia. The manager of Nottingham Forest dubbed his star player “a bloody poof”. Even his own brother John Fashanu tried to bribe him with £75,000 not to come out, and later distanced himself with an exclusive interview headlined “My gay brother is an outcast”.

He continued to play football at senior level until 1994 but was a target of constant abuse on the pitch, and it wasn’t long before his career began a downward spiral.

“Justin was blindsided by the backlash and the ‘heavy damage’ that coming out inflicted on his football career. He received homophobic abuse from some fans,” recalled the veteran LGBT+ activist Peter Tatchell.

“Like many Black footballers in those days, he was subjected to racist taunts by fans from rival teams. They would make monkey noises and gestures, and throw bananas onto the pitch. But it was anti-gay prejudice that ultimately dragged him down.”

The final blow came in 1998 when he was questioned by police after a 17-year-old boy in America accused him of sexual assault. The age of consent was 16, but homosexual acts were illegal in Maryland at the time.

Fashanu maintained that the encounter was consensual but feared he would never get a fair trial due to his sexuality. He took his own life on May 2, 1998, aged just 37.

Homophobia is a pervasive problem in football to this day – but change is happening.

While the landscape of LGBT+ rights has changed vastly since Justin Fashanu’s death, few of those changes have been felt in the world of football.

The legacy of Fashanu’s treatment continues to hang over the sport, as evidenced by the fact that no elite gay footballers are willing to come out while still playing.

This worrying lack of diversity was recently highlighted by Aston Villa Women’s sporting director Eniola Aluko, who claimed that a number of Premier League footballers have come out as gay to team members while continuing to hide their sexuality in public.

Although individual clubs have attempted to push back against anti-gay sentiment, the spike in homophobic slurs at matches indicates there’s a long way to go.

Unfortunately the same is true of the media, which continues to mistreat gay men in much the same way as it did Justin Fashanu.

Last year, Gareth Thomas – the former Welsh Rugby captain and first rugby player to come out – said he was forced to reveal his HIV positive status after a newspaper threatened to out him. He later added that a journalist had been the one to break the news to his parents.

However, there is a glimmer of hope. There are a number of sportsmen who have come out as queer to a much more positive reception, among them ex-Bath and England rugby player Levi Davis, who recently opened up about his bisexuality.

Last month over 200 LGBT+ allies and organisations condemned the “sensationalised” media coverage of closeted gay and bisexual footballers in an open letter that urgently called for more empathy and understanding.

“If we are to help LGBT+ people in our sport who are struggling to arrive at their own sense of Pride, while also avoid fuelling speculation about who is and isn’t gay or bi, then greater transparency and a more constructive approach is required from the game’s critics,” they wrote.

They warned that the media’s “sensationalised accounts of agony and anguish” give the perception that complacency has set in on homophobia in football, when the push against it is stronger than ever.

“The truth is that there has never been a more concerted team effort to tackle prejudice, but its progress is hampered by such accounts and makes gay and bi people across the men’s game feel less safe and less likely to feel they can be honest and open about their identity.”

Referee Michael Oliver wears the Stonewall rainbow boot laces at a Premier League match as part of the campaign to tackle homophobia in sport (Catherine Ivill/AMA/Getty)

Many efforts have been focused on the prevalence of homophobic chants in the stands, with Thomas lobbying for them to be added to the Football Offences Act just as racist ones were in 1991.

Earlier this year the government finally agreed to make the abuse illegal after a group of cross-party MPs voiced their dismay at the “slow progress in kicking out homophobia from football”.

Meanwhile, Justin Fashanu earned his rightful place in the National Football Museum’s Hall of Fame on what would have been his 59th birthday. The prestigious honour was received by his niece Amal Fashanu, who has become a prominent campaigner against homophobia in her uncle’s memory.

Three months later, Amal met with the Professional Footballers’ Association to discuss the best way to support seven gay footballers and help them make the first steps towards coming out, when they are ready.

“For a long time the game has been ignoring the issue,” Amal said. “But at long last this appears to be changing.”