A mass testing revolution could finally end Britain’s HIV crisis – and soon, say former Tory health minister and Labour MP

(Stock photograph via Elements Envato)

HIV testing should become a routine part of healthcare conducting on an opt-out basis, the UK’s independent HIV Commission has recommended in a report released on World AIDS Day.

Conservative MP and former health minister Steve Brine and Labour MP Wes Streeting, both members of the commission, told PinkNews in a joint interview that the renewed push is needed to reduce HIV transmissions by 80 per cent by 2025, and eliminate new transmissions entirely by 2030.

With talk of R rates, viral transmission and large-scale public health interventions becoming common parlance over the past year, their case for action feels more familiar than ever.

Labour MP Wes Streeting and Tory MP Steve Brine, members of the HIV Commission

Brine says: “If there’s three words sum up what the commission is about, it’s test, test, test. And that would have seemed like a slightly alien thing to say before this year, but if ever there was a year where we can land that message well, I would have thought it’s 2020.”

Of the estimated 105,000 people living with HIV in the UK, around 6,600 people are undiagnosed and could be at risk of infecting others without knowing it.

Not dissimilar to the test, trace and isolate approach to COVID-19, a routine test and treat strategy could prove effective at controlling HIV, with those on effective treatment unable to pass the virus on.

Fresh solutions to an old pandemic.

Streeting says: “One of the things that we really hope will come out of our recommendations is the normalising of HIV testing on an opt-out basis.

“It should just be routine. When you go to sign up with a new GP, they ask you about your previous health conditions and they take your weight and they ask you how many units of alcohol you drink a week, and everyone lies. These are normal parts of signing up for a GP. Why wouldn’t you do an HIV test?

COVID has underlined the importance of testing and public health interventions. (Leon Neal/Getty)

“People go for blood tests all the time, and there’s no stigma about that. Why wouldn’t we test for HIV at the same time?”

Brine adds: “One of the beacons of hope in this is maternity testing, where this has been the norm for years. We’re at 100 per cent, testing pregnant women when they give birth as to whether HIV is passed on to the baby, and that has become completely the norm, stigma free. That’s a great example of where I think we can get to.”

While money is no object when it comes to coronavirus, the same has not always been true for HIV, with public health budgets straining under a decade of cuts and cash-strapped local authorities forced to reduce sexual health offerings.

Brine, who oversaw budget reductions as a health minister under Theresa May from 2017 to 2019, knows this better than most.

He admits: “The cuts to the public health budget over the last 10 years are deeply regrettable. It’s not the case that I can say that I sat there in office and that was that was something I was happy to do.

“It was an economic necessity. But times have changed, and actually we are calling for increased investment in the public health budget and in the sexual health budget.”

HIV-preventing drugs present a valuable tool.

The minister was also in office during disputes about funding for pre-exposure prophylaxis, known as PrEP, a drug regime recommended for at-risk groups including gay and bisexual men and trans women that can prevent HIV infection.

The years-long row turned ugly in 2016 when NHS England declined to fund the treatment, arguing it was the responsibility of already-struggling local authorities.

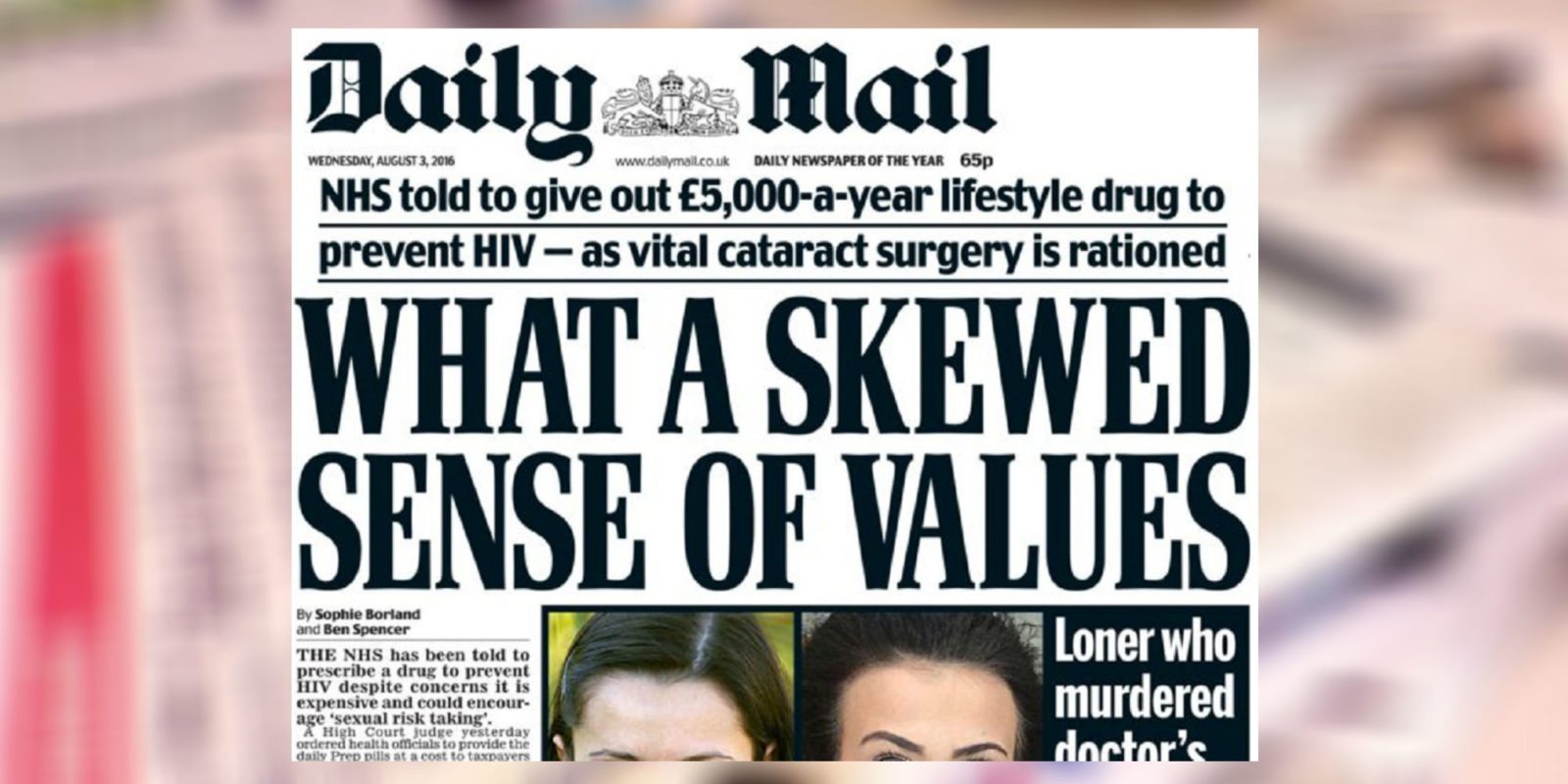

Front-page headlines ran across right-wing media outlets, briefed by unidentified sources, claiming PrEP would deny treatment to children with cystic fibrosis and rob elderly cataract patients of surgeries.

The impasse was only resolved after a successful legal challenge brought by HIV campaigners, with PrEP finally rolled out fully in England in October after a lengthy trial period.

Brine says: “I was incredibly frustrated when I was in office about the slow rollout of PrEP. It was totally unacceptable.

“I was very pleased with the outcome of the legal challenge when it happened. We shouldn’t just think, though, just because PrEP is now being agreed and commissioned, that it’s all okay.

“There are still big issues with people accessing PrEP, but it’s a really important part of this toolbox, and a really important part of giving hope that we can get to where we want to get to.”

The Daily Mail ran a front-page story attacking PrEP.

Streeting notes: “We know of 14 gay and bisexual men on the PrEP waiting list who became HIV positive, no doubt there are more. But you know, for those people who were on the waiting list, I can’t imagine how angry they must feel. That kind of underlines the urgency of the commission’s work.

“Doing this work, and doing it urgently has the potential to be life changing for people. And the consequences of failure are serious for people whose lives are detrimentally affected as a result.”

What ‘bean-counters’ get wrong about tackling HIV.

While arguments of money are often advanced by vocal opponents of HIV prevention work, both Brine and Streeting stress that interventions save money in the long run.

Streeting explains: “Modelling [shows] that over £200,000 in future health care costs are saved per person who is diagnosed and linked to the right treatment and care.

“Imagine how much money we will be saving, not to mention the lives we will be changing for the better, by eradicating HIV transmission. Even the hardest-headed bean counters in the Treasury should be persuaded that this is a sound financial investment.”

Brine agrees: “We know that the cost of treating the condition at later stage is double what it is if treated early, and if you get the relevant antivirals you can’t pass it on. So it makes every financial sense to do that. There is a financial argument and the health argument and a social justice argument to what we’re suggesting.”

The most recent data on HIV/AIDS largely paints a rosy picture. Gay and bisexual men, who make up just under half of all people living with HIV, have seen drastic reductions in infection rates, with the UK becoming the first country in the world to meet previous UN targets for diagnosis and treatment in 2018.

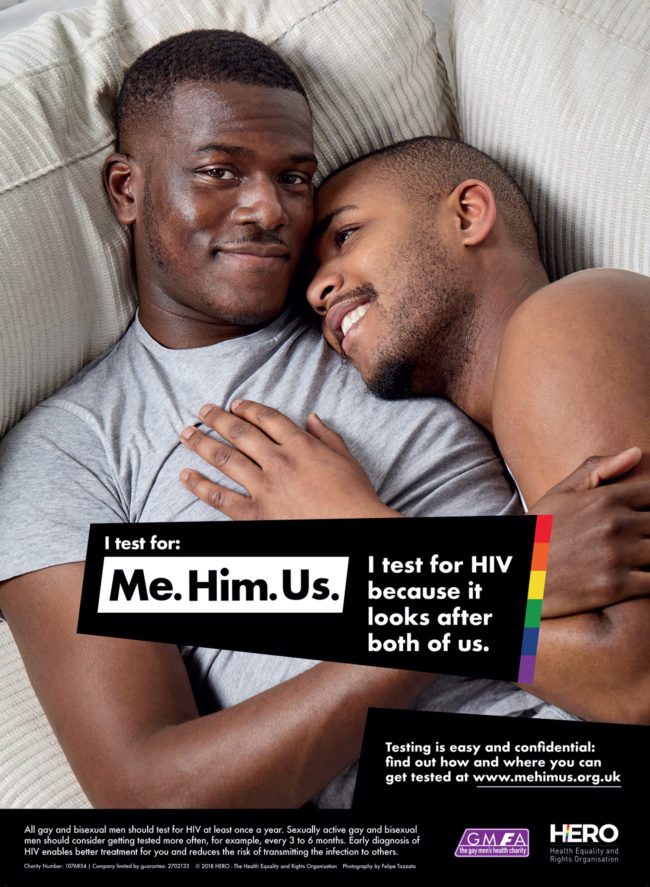

However, Black gay and bisexual men remain disproportionately affected by HIV, while trans women are at risk but are often left out of research and messaging.

Black gay and bisexual men remain disproportionately affected by HIV (GFMA)

Brine says: “We’ve seem the problems with COVID, in BAME communities, where that they said, ‘Well, you just didn’t put it in our language, you didn’t talk to us’, and we’re still making that mistake.”

Streeting adds: “The reason why we’ve got a target to reduce transmissions by 80 per cent by 2025 is because we recognise that it’s going to be the last 20 per cent that is going to be the most difficult and where most work is going to be required.

“So we’re trying to front-load the progress we need to make in the first half of the decade. Recognising that, and getting to the final destination, is going to be a challenge and is going to require some really detailed and focussed work.”