Queer Black lives on screen: A brief history of the good, the bad and what needs to come next

From Jason Holliday and Paris is Burning to Pose and The Wire.

From the Hays Code era to Moonlight and Pose, on-screen portrayals of queer Black lives is an ongoing journey.

On-screen representation has taken much-needed leaps in recent years, with queer Black lives being illustrated in all their messy, three-dimensional glory on shows such as Pose, Orange is the New Black and Sex Education, and to a lesser extent, on the big screen, in films such as Moonlight.

In January, GLAAD reported that 23 per cent of queer characters on broadcast TV were Black, with a higher percentage on cable and a lower percentage on streaming.

However in film, just two of the 20 LGBT+ characters who appeared in major studio released were Black. While progress is happening, it’s clear that there remains a long way to go.

As screenwriter and director Joseph A Adesunloye puts it: “Yes, Black queer representation on-screen is enjoying a long-overdue moment as we as queer Black people get a chance to tell our own stories, in our own image.

“But getting the funding and support as a queer Black filmmaker is hard. Getting funding for queer Black stories… even harder.”

Dyllón Burnside as Ricky in Pose. (FX)

Hollywood’s relationship with Black narratives has its own distinct and damaging history, not least the ongoing appetite for films such as 12 Years a Slave and The Help.

Such reductive representation of Black people relied upon consistent tropes – heterosexual Black men as either strong and hypermasculine, Black women as unbreakable caregivers, and gay Black men as femme and sass – all of which obscure the multitude of ways we actually show up in the real world.

The history of all queer representation on-screen (or lack thereof) starts somewhere within the film industry’s self-imposed Hays Code.

Introduced in 1934, it laid out a set of guidelines for all motion pictures. The code prohibited many things, including ‘sexual persuasions’ and ‘sex perversion’ which was understood to include homosexuality, and TV studios followed.

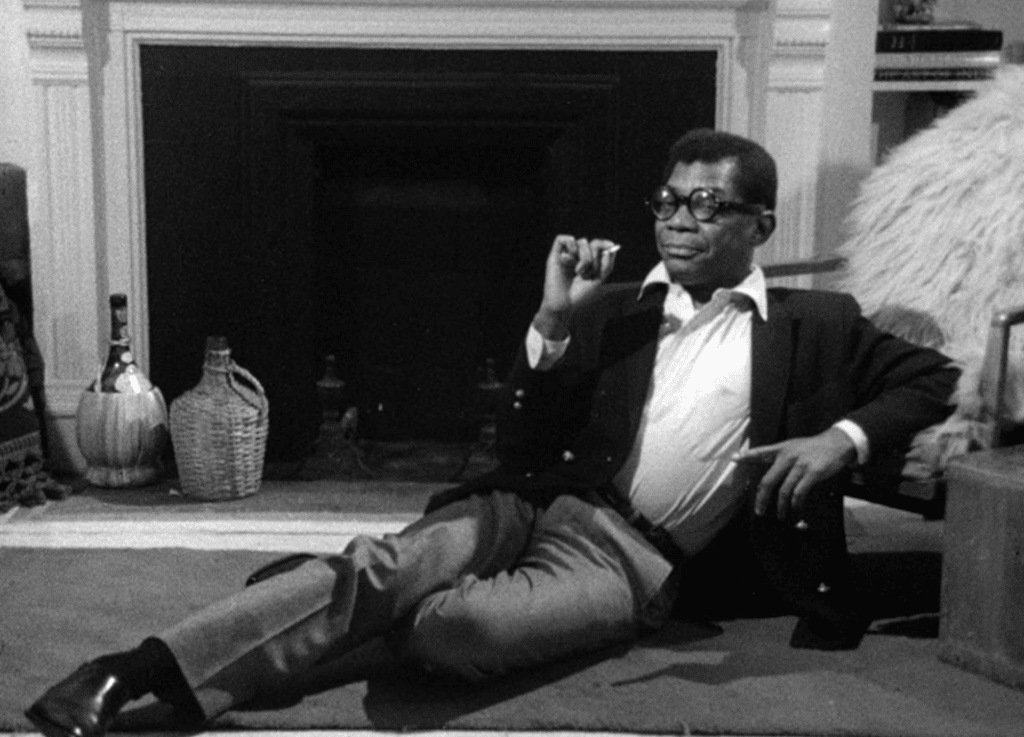

Outside of the Hollywood machine these rules weren’t always considered, like 1967’s Portrait of Jason, a documentary following openly gay Black entertainer and sex worker Jason Holliday.

Jason Holliday in 1967’s Portrait of Jason. (IMDb)

And as Cabaret screenwriter and critic Jay Presson Allen said in the 1995 documentary The Celluloid Closet: “The guys that ran the Code weren’t rocket scientists.

“They missed a lot of stuff and if a director was subtle enough and clever enough, they got around it.”

One of these enduring workarounds was queer coding: the subtextual coding of a character in media as queer, without explicitly confirming their sexuality.

Queer coding led to an array of queer-coded stock characters such as The Villain: bitchy and mean – think The Lion King‘s Scar.

Most enduring is The Camp Sissy – flamboyant, weak men who viewed women through a non-sexual lens, like In Living Color’s Blaine and Antoine.

While queer coding enabled an expression of queerness to subvert the Hays Code, it eventually became limiting. Over a span of 90 years, queer coding reduced gay men to the same fatigued cliches and reinforced harmful narratives about queer people.

Representation in the media, as we now know in 2021, is integral to how we all navigate the world. The plethora of TV, streaming, and Academy Award-worthy narratives we see today celebrating queer Black stories, and what has come before, only really broke through, perhaps, 20 years ago.

A precursor, and one of the most notable pieces of representation in the 1990s, was Paris Is Burning: both a celebrated and controversial film. Without it, we may not have more innovative and needle-moving productions like 2016’s Kiki or Pose; on the other hand, many of the documentary’s participants felt Jen Livingstone’s seminal work was voyeuristic, with none of the profits from the film going to the communities within it.

The turn of the millennium marked a significant shift in queer Black representation on film, as the Hays-era tropes start to be replaced by more nuanced storytelling, with queer Black people writing, directing, and producing.

Standouts include Jewel’s Catch One and Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin, both of which profiled queer Black elders; and 2005’s The Aggressives, which explored identity through the lens of Black trans men and Black butch lesbians.

On television, in 2002, HBO’s The Wire put forward trope-defying character Omar Little: a fearless, unapologetically gay, hyper-masculine gangster who robbed drug dealers.

Michael Kenneth Williams as Omar Little in The Wire. (IMDb)

That same year The Shield gave the world DL (‘down low’) Detective Julien Lowe, played by Michael Jace, and thus offered another complicated representation of a queer Black man.

Both characters, Omar Little and Julien Lowe, challenged the audiences and ignited discourse in Black spaces and beyond about what gay men look, sound, and act like.

They ushered in never before seen portrayals of gay Black men as nuanced, and which existed outside of the stereotypes and cliches that had so persistently been imposed.

Williams went on to portray other trope-breaking gay characters, such as the Vietnam veteran Leonard Pine in Hap and Leonard, the HIV-positive activist Ken Jones in When We Rise, and most recently, Montrose Freeman in 2020’s Lovecraft Country.

In 2005, the Logo network launched the first scripted series to centre a group of Black gay men, Noah’s Arc.

On the show, The Sissy, the DL, the Hyper-Masculine, and all the other types of personalities existed as they were, in the context of a community brought together by their sexuality and their race.

Importantly, Noah’s Arc leaned into narratives about relationships, intimacy, STIs, and more – and all through a queer Black lens, in front of and behind the camera.

In 2016, something remarkable happened: Moonlight, directed by Barry Jenkins (who is straight) became the first LGBT+ film and the first film with an all-Black cast to win the Oscar for Best Picture.

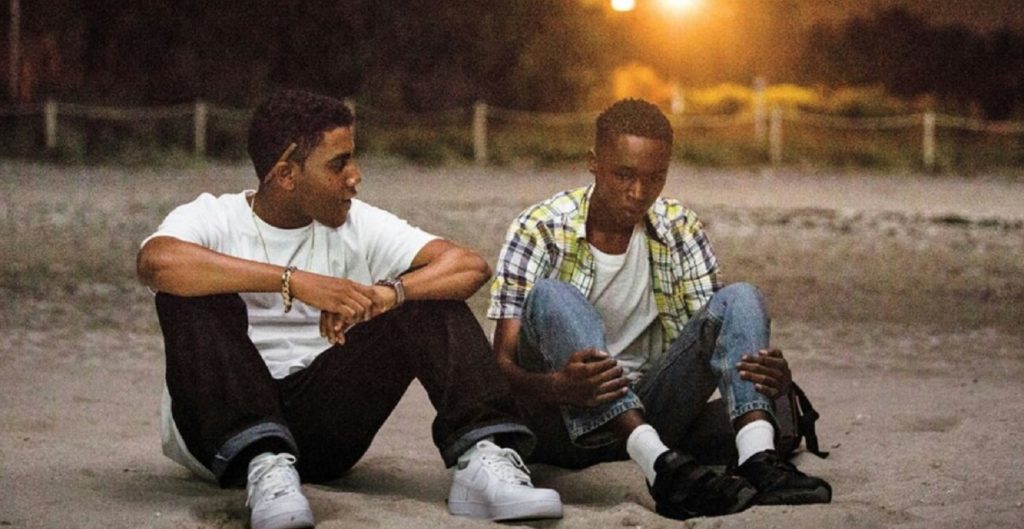

Moonlight. (IMDb)

A film centred on a young, gay Black man in Miami’s housing projects, Moonlight follows Chiron, played by Ashton Sanders, Alex Hibbert, and Trevante Rhodes, as he learns to navigate the world and how he chooses to reclaim power, control, and security.

While its budget was $1.6 million, tiny by Hollywood standards, its $65 million worldwide gross showed an appetite for queer Black narratives.

Today, Netflix’s Sex Education stands as one of the streaming platform’s big successes, and Eric Effiong, played by actor Ncuti Gatwa, is perhaps the most prominent gay Black character on screens today.

An emotionally mature, complex, and relatable character, he never feels like a mere token within the narrative.

His life, alongside those of his friends, is given meaningful, modern consideration which offers more substantive representation for queer Black audiences globally.

Ncuti Gatwa plays Eric Effiong in Sex Education. (Sam Taylor/Netflix)

And while great strides in representation have been made, there’s much more to do. In the UK, authentic queer Black representation is still very much a work in progress.

The BBC’s EastEnders is renowned for its disposable queer Black characters, the first – Della Alexander – appearing in 1994. The most recent, Tosh Mackintosh, was a domestic abuser, portrayed by Rebecca Scroggs, and did little to offer audiences a positive portrayal of the queer Black people and families that exist in the world.

In the last year, I May Destroy You and Years & Years have provided two rare examples of layered portrayals of the queer Black experience, but British viewers are still faced with a dearth of representation.

Despite the good, the bad, and what may need to come next, the reality is there is no definitive way to depict queer Black narratives on screen.

The queer Black experience is not a monolith, and this should present a golden opportunity to boardroom-level decision-makers, a chance to show the world as it really is: filled with a kaleidoscope of queer Black stories.