Trans academics on being silenced, outed and worse at university amid anti-trans Kathleen Stock row

Students at the University of Sussex protesting against Kathleen Stock. (@AntiTerfSussex/Instagram)

With the resignation of professor Kathleen Stock from the University of Sussex after weeks of peaceful student-led protests against her employment and her trans-exclusionary views, the situation for trans people in UK universities has come into renewed focus.

Trans and non-binary students – including those at Sussex, who hailed Kathleen Stock’s resignation as a “monumental victory” that would make the campus safer for trans students – face harassment and discrimination at British universities.

Worryingly, the discrimination that trans students face comes not just from fellow students, but from their lecturers and professors, too – more than a third of trans university students will have experienced negative comments or conduct from staff in the last year, according to a 2017 Stonewall report into being LGBT+ in Britain.

And, presumably partly because of this, one in seven trans university students will drop out, or consider dropping out, before the end of their degree.

University of Sussex professor Dr Kathleen Stock has faced criticism for her anti-trans views.

The same year, the situation for trans students was briefly looked into by the government’s National LGBT Survey – the largest-ever national survey of an LGBT+ population. It found that teachers and teaching staff were notably more likely to have been reported as perpetrators of sexual harassment or violence by trans students (11 per cent) than by cis students (five per cent), although this statistic includes schools and colleges as well as universities. Still, the few available statistics indicate that going to university is tougher for people who are trans.

However, when it comes to the experiences of trans teachers and academics, there is even less research. There is no good data on the number of trans academics in the UK, their career paths or their influence.

But trans academics, and the experiences they have teaching in UK universities, show us another side of being trans in higher education. Trans academics are the peers and colleagues of transphobic academics; work in the same institutions; must face the question of whether to speak up or stay quiet when transphobia on campuses spirals to protest-worthy heights.

With the data lacking, PinkNews spoke to two trans professors to find out what their experiences could tell us about being trans and working in higher education.

‘Most trans people don’t have any voice’

Alex Sharpe is a barrister and law professor at University of Warwick. She’s at pains to point out her experience of being a trans person in academia is “not particularly representative” because she was a professor when she transitioned.

“I can understand early-career scholars being concerned about it [being open about being trans when applying for jobs] in this current environment,” she says.

Several trans academics, more junior than Alex, were reluctant to speak about their experiences at work when contacted by PinkNews – citing fears of a negative reaction from colleagues, or unintended impacts on future job opportunities.

While Alex may be in an atypical position, it means she is confident in speaking about her experience publicly. “I have more voice than many,” she says. “Most trans people don’t have any voice.”

Alex thinks people working in academia are “not generally hostile to trans people, but many of them are quite naïve about the political situation in which trans people find themselves”.

“Most are unwilling to do the work required to understand this situation and some are more interested in maintaining a virtuous self-image, as champions of ‘free speech’ and so forth, than they are about thinking through complex relationships of power.”

Alex Sharpe is law professor at Warwick University. (Supplied)

Alex is speaking before Kathleen Stock quit the University of Sussex, but during the weeks-long student-led protest against Kathleen Stock’s employment and her anti-trans views.

Asked how she thinks it might feel to be a trans student at a UK university, Alex hesitates. “Over the last few years, I have received countless emails from trans and non-binary students, especially in the UK,” she says. “They are always very complimentary about my work and activism, which is very gratifying. I’m very aware as a university professor with some public profile, I give these young people hope and voice.

“All these missives emphasise how difficult it is to be trans in our society, including at university.

“While I can remember a time when transphobia was a less present concern, especially on university campuses, young people entering university today know nothing else. Their teenage years have coincided with a war of attrition waged by our media against their very being.

“And in the face of this onslaught, they are far from reassured by academics who appear to care more about lofty principles than their human dignity and ability to thrive.”

‘It’s a concrete ceiling, if you’re trans’

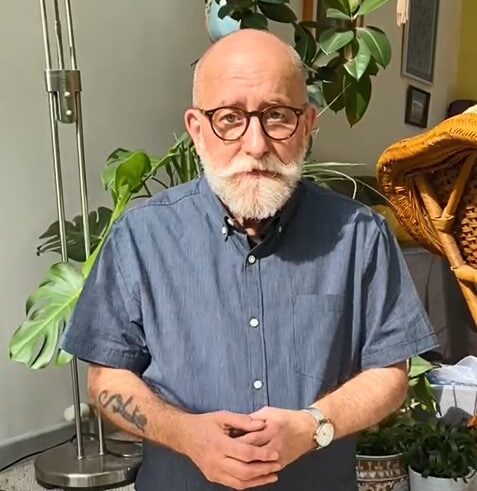

Stephen Whittle is professor of equalities law at Manchester Metropolitan University. He transitioned 47 years ago, aged 19, and has been openly trans for his whole academic career, which began with working as a tutor at the Open University in 1990, when he was 35. Stephen moved to MMU in 1993 and has taught there ever since.

When Stephen was an undergraduate student at University of Sussex, he was outed by the dean of the university. “He called me into his office and said, ‘Why did you lie on your application form,'” Stephen remembers. “I said, ‘What?'”

The dean had read the name of the school Stephen had put down on his application and realised that it was a girls school. “I said, well, that’s because I’m trans,” Stephen says. “Within hours, it was everywhere. Even though I’d asked him, very specifically, not to disclose.

“I was walking down the corridor, someone made a joke about sex, somebody else grabbed me and groped me.”

Stephen Whittle, professor of equalities law at Manchester Metropolitan University. (Supplied)

Stephen ended up taking a year out of university, trying to work out “how to deal with this”. He worked as a builder but after being diagnosed with MS realised he couldn’t continue in construction indefinitely – so he went back to university, doing evening classes in law for five years to earn his degree.

After a masters and a PhD – on “transsexual people and the law” – Stephen began trying to get work at a university. He struggled. While he was still doing his PhD he got a post at MMU, and there he’s stayed ever since – “primarily because no one else wants me”, he says. “Nobody else will employe me, nobody else will even shortlist me for posts. Posts that should have been mine went to people with less experience and fewer qualifications, at that time.”

He explains: “It’s a concrete ceiling, if you’re trans.”

Stephen says he’s very fortunate that MMU has “recognised that I do the job well and I’ve done the publications” and as a result he’s been “promoted through the system”

“It’s not been an easy ride for anybody,” he admits, “the university included.” Early in his time at MMU, Stephen had students shout abuse at him during lectures, or walk out and refuse to be taught by him.

Asked if he thinks these things would still happen today, he says yes. People still try to out Stephen to his students all the time – with limited effect, as one of the first things he does with new students is tell them that he’s trans, to get it out of the way. “If they’ve got questions they can ask me, instead of talking f**king rubbish behind me back,” he says. “One time, an electrician came into the classroom. He waited until the students came out and then told them all, did they know their teacher was ‘really a woman’. They said, of course, he told us in our first lecture.”

“I’m not hiding. I’m not pretending to be somebody I’m not. But it’s been disheartening, to say the least, to feel that we don’t have a glass ceiling, we have a concrete one.

“We’re picking away at it, but I just have to accept that I was born 30 years too early.”