Alina Khan on banned trans love story Joyland: ‘I always hoped I would find a place for myself’

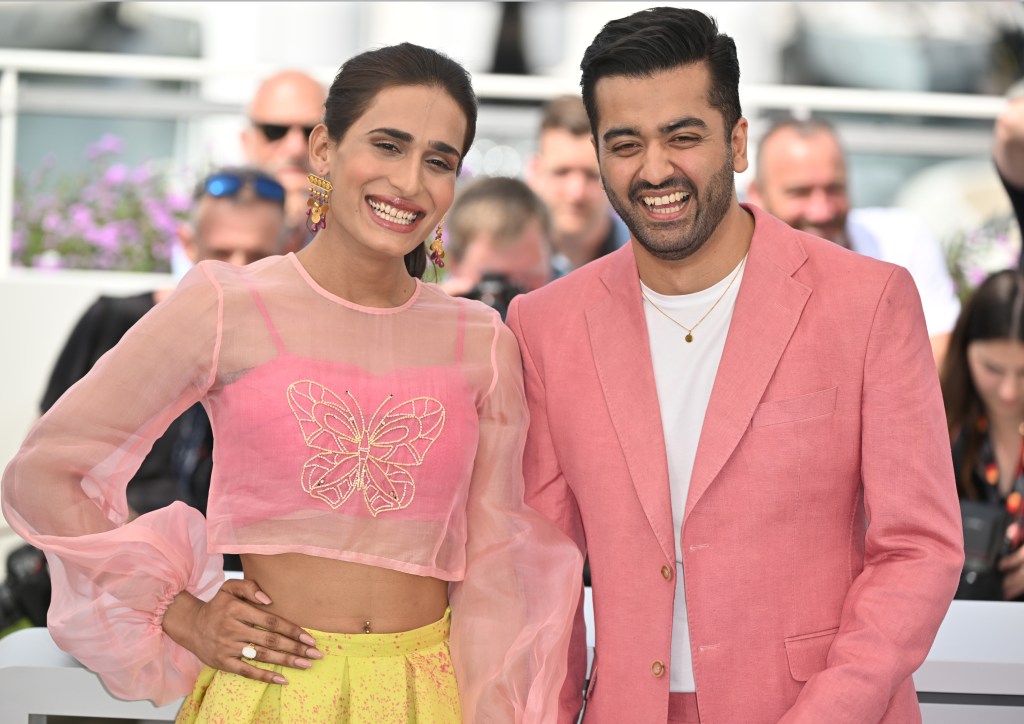

Joyland: Alina Khan and Saim Sadiq (Getty)

Groundbreaking Pakistani drama, Joyland, tells the story of an unexpected romance. Here, director Saim Sadiq and its star Alina Khan talk religious censorship, defying stereotypes, and blazing a trail for trans representation.

First-time filmmaker Saim Sadiq is having quite a time of it with his debut feature Joyland. Having scooped the prestigious Un Certain Regard jury prize at the Cannes Film Festival and gained the support of Oscar winner Riz Ahmed and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Malala Yousafzai as executive producers, the film made history back in December when it became the first Pakistani film to be shortlisted for the Academy Awards.

But although Joyland has seen international success, the journey has been anything but easy for those involved into bringing its story to life. Set in bustling, inner-city Lahore, the drama, which depicts a love affair between a married man and a trans woman, was banned in Pakistan last August following pressure from hardline Islamic groups who called it “repugnant”. Although the decision was overturned mid-November, the ban still remains in force in Punjab, where the film is set.

Much like its namesake, a popular amusement park nestled among the busy streets, Joyland thrills and surprises with its story of Haider (Ali Junejo), a struggling husband to Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq), who takes a job as an erotic dancer to provide for his family. Immediately drawn to the captivating Biba (Alina Khan), a member of the khawaja sira (third gender) community and an aspiring trans star, he soon finds himself caught in a love triangle that has far-reaching consequences.

Before religious censorship and Oscars recognition came calling, however, director Saim Sadiq was simply focused on creating a film showing the humanity of the trans community. Back in the beginning, he enlisted the help of a trans consultant and spoke to “as many trans women as possible” in order to portray the community authentically.

“I just sat and listened about their life, their background, their aspirations, what scares them, what drives them,” he recalls. “This gave a holistic experience, but I also used individual examples; how they differed from each other because they are not a monolith.”

It was these conversations that gave him the confidence to make Biba a “bossy and not always likeable” character. “Why do they always need to be a people-pleasing, sweet woman? As I spoke to more and more, I thought, ‘Why not make her a badass who doesn’t want people’s approval?'”.

Enter Khan, who gives an electrifying performance as the feisty, complicated Biba. Although Khan and Sadiq previously worked together on the Venice-winning 2019 short Darling, a film with a similar premise to Joyland, Sadiq admits that when he first saw Khan’s audition it was “not very good”. However, after meeting and seeing her “comfortable, easy and charming” nature, he decided to take a chance.

In any case, the pair look back fondly upon their working relationship, and Khan jokes that the pair of them have come “a remarkable way” since she made her screen debut.

“After Darling came other opportunities and I have worked very hard for them,” she explains. “I would practice on the sets, then [go] home and practice even more.

Unlike Khan, who Sadiq affirms is the “sweetest person in the world”, Biba is “brash, abrasive, [a] storm of a person who completely hides their vulnerable side.”

“The different thing [about Biba] is she is a woman who wanted to fight for herself,” he explains. “Another thing that sets this apart from anything else that I’ve seen, is the trans person in the film is part of a bigger storyline. She’s not just a character to be ridiculed, but her life impacts other people. All trans people have had struggles in their life and we’ve all been through a lot. This film is giving us an opportunity to show a strong woman.”

Joyland certainly doesn’t shy away from exploring topics seldom seen in Pakistani media, ranging from mental health issues and the trappings of patriarchy, to sexual desire and the resilience of the most vulnerable in society who are simply trying to live a peaceful life.

“We chose to fight for the film, but that obviously came at a cost”

While Joyland focuses on the love affair between Haider and Biba, one of the its greatest achievements is the characterisation of Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq), Haider’s smart, independent wife, who is depicted with great sensitivity. After Haider begins to earn money, Mumtaz is pressured into leaving her job as a makeup artist at the beauty salon, reflecting the fate of countless Pakistani women for whom producing a male heir remains their sole purpose.

Although Biba and Mumtaz fall on opposite sides of Haider’s affections, the film doesn’t make the mistake of pitting the two against one another. Instead, we see both characters for all their faults and virtues, fighting against a rigidly patriarchal society which refuses to afford either the status and social identity they deserve.

Although Joyland did not make it through to the final Oscar nominations, the film, which is the first major Pakistani motion picture to feature a trans actor in a lead role, has already had a tangible impact upon the TV and film industry there.

“One thing that has happened already is a shift in the way we look at gender stereotypes,” says Sadiq. “Mainstream television shows, which glamorised domestic violence [and] the subjugation of women, [and] played into the mockery of transgender people for many many decades, are now using a more critical and empathetic lens.”

Khan agrees. “I’m so pleased the film, showing the culture, diversity and struggle of Pakistani people, is being shown internationally and that Saim gave the opportunity to represent the trans community in an accurate way. It is so rare to have this opportunity in Pakistan and if we do, often it is not actual trans people who are given these roles.”

There’s no denying the fact that the film is still highly controversial, though, especially given the ban enforced by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting in Pakistan, who said it contained “highly objectionable material” which went against “decency and morality” when it cancelled the film’s license.

“We chose to fight for the film but that obviously came at a cost,” says Sadiq. “We offered our mental health to other people to take for a ride. Physical safety-wise, I ensured Alina was not a part of the fight.

“I was like a headmaster telling her what to do because I was really paranoid, even though she wanted to. She’s the most vulnerable out of all of us, she would become the easiest target.”

The rest of the cast, including well-known faces in the industry such as Sarwat Gilani and Sania Saeed, bore the brunt of the anger.

“They did receive some serious threats. They had to hire guards and just carried on. Now we are all slowly recovering from that”.

While the ban was eventually reversed around most of the country, the film remains banned in Punjab. Although the producers of Joyland subsequently filed a petition to the Lahore High Court challenging the ban, the process has stalled due to the volatile political climate.

“The Punjab government collapsed a few weeks ago, so, generally speaking, it is a political s**tshow,” Sadiq explains. “We’re at the centre with our film, hoping whoever is in charge can please take a look.”

Despite the controversy, Sadiq says he was totally taken aback by the backing of Riz Ahmed and Malala Yousafzai, whose support was “kind and generous but totally unexpected”.

“After it premiered in Cannes, we sent them both links to watch it, with no other intention than just wanting them to [see] it. It was enough for them to watch something we made and hopefully like it, but they loved it. They wanted to enhance the profile of the film”.

Joyland has already made waves in the UK, and Sadiq says it “means so much” that it has resonated with a mainstream audience where there is a significant diaspora community. He’s also hopeful that while South Asian viewers will relate to the challenges many of the characters in the film have to face, awareness will also be raised that will in turn help to break stereotypes.

“I’ve noticed that sometimes diaspora carry a lot of baggage around who they are,” he says. “They are very used to straddling between two identities – the identity of where you came from and of what home is now.

“The film is, in many ways, about all these characters, straddling dual identities. About what they desire for themselves and the contrast with what society expects from them.”

Khan, who is all too familiar with the struggles facing trans and gender non-conforming people in Pakistan, also hopes that the film will serve as a route map for those navigating their gender identity. The actress was initially rejected by her family when she came out as trans, but they have since accepted her following the success of her acting career.

“As a child, I always dreamt of acting and would wonder, if I ever got the chance, whether I would be cast as a male or female character,” she reflects.

“However, in my childhood I ran away from home to fend for myself on the streets. I was still trying to understand my identity when I started to perform in functions, alongside a basic computing course. Eventually I had to put money over education to get by.”

Despite facing abuse and exploitation, Khan is determined to represent the trans community, and is pleased that Joyland has brought her both acceptance among her family and industry visibility.

“I feel blessed, especially now my family has accepted me. As difficult as it was to come out, if I had not pursued this path I would have just ended up in a small room inside my home.

“I always hoped that one day my family would accept me and I would find a place for myself in society”.

Joyland is in UK cinemas now.