Booker Prize nominee Eva Baltasar on breaking boundaries in lesbian motherhood novel Boulder

International Booker Prize longlisted author Eva Baltasar. (EB Ruano/And Other Stories)

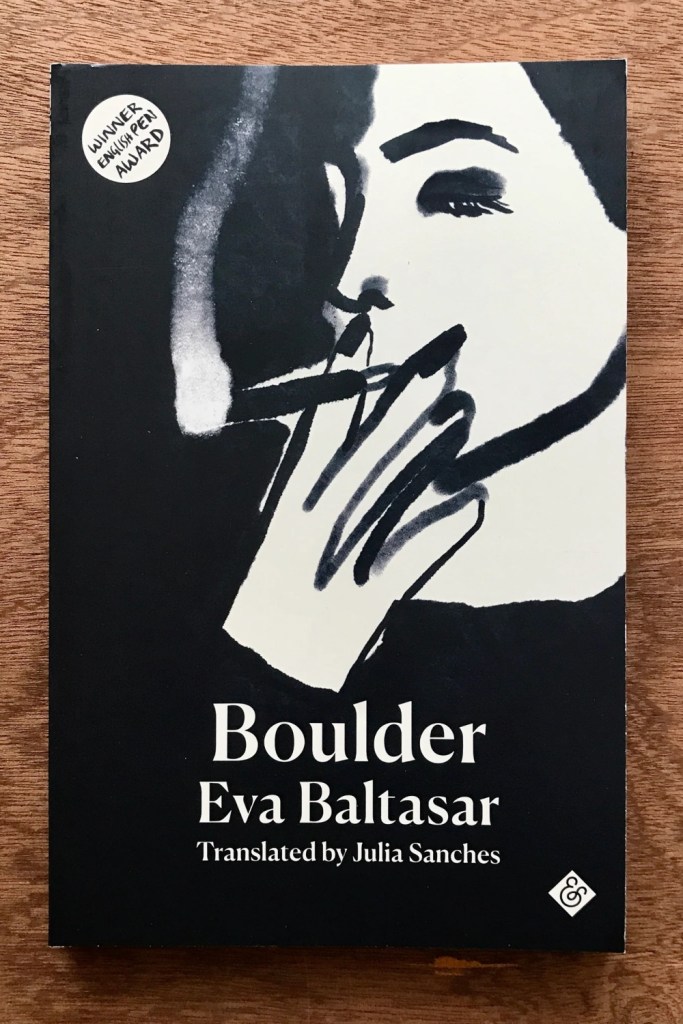

In a PinkNews exclusive, Spanish author Eva Baltasar discusses queer representation and sapphic motherhood in her International Booker Prize longlisted novel, Boulder.

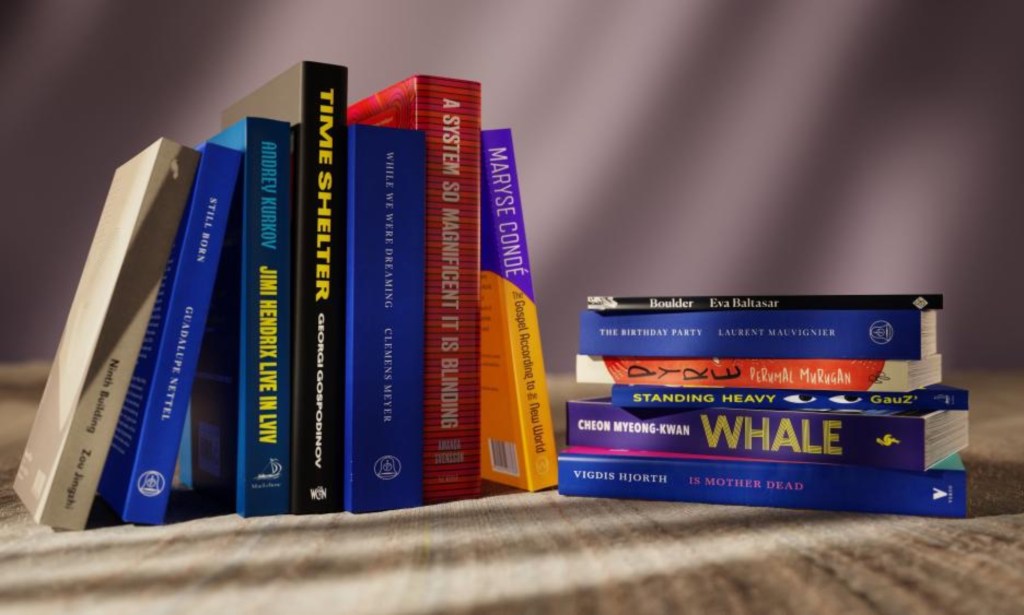

With 13 prizes, 10 volumes of poetry and three novels to her name, it’s no exaggeration to say that Eva Baltasar is a literary powerhouse. So it feels right, then, that the celebrated writer has now recognised among the greatest literary talent the world has to offer, with her latest novel making the coveted longlist for the 2023 International Booker Prize.

The prize has long been home to industry titans, boasting names such as Poland’s Olga Tokarczuk, The Vegetarian author Han Kang and multi award-winning Philip Roth among its alumni. This year Baltasar – the first Catalan author to make the list – joins works heralding from places as diverse as Mexico, Norway and South Korea.

But in little more than 100 pages, Boulder is trailblazing in more ways than one. As the only LGBTQ+ book in the running this year, it touches on a subject seldom found in prominent literature: sapphic motherhood.

Baltasar, whose first poetry collection, Laia, was published in 2008, is now a pre-eminent voice in the queer book world, but still feels humbled.

“I’m left with a feeling of deep gratitude for all the people who, without my knowing, helped Boulder get on the long list,” she tells PinkNews, giving special mention to the novel’s translator, Julia Sanches.

The book’s main character is a cook on a merchant ship, nicknamed Boulder by fellow-traveller Samsa, and the two women quickly falls in love with. When the couple decide to move to the Icelandic capital Reykjavik, Samsa announces that she wants to have a child.

Despite some reluctance, Boulder supports her partner’s wish to become a mother but as lovers turn to strangers, and Boulder evaluates the sacrifices of being a mother in modern-day society, her life begins to unravel.

Baltasar is thrilled “not only to be giving voice and visibility to [the LGBTQ+] community but also to all the people and communities who, for whatever reason, feel uncomfortable living in our society or have no choice but to struggle through every day just to be true to who they feel they are.”

‘I tried to create a character to be the hand that shapes the soul and maps out a story for the body’

The author is all too aware that reading is not just a passive act but one that inspires, saves lives and broadens horizons. For her, telling nuanced queer stories not only “normalises” them but “affects real life, society and the world around us”.

And she is simply paying forward her gratitude to the pioneers who came before her, not least Virginia Woolf, whose book, Orlando, she received on her twelfth birthday, giving birth to a “long lasting love”.

Given her background as a poet, Baltasar’s work is filled with lyricism, gutting emotion and deep introspection, only made clearer as she talks through her writing process. “The initial impulse behind this book was to get to know a woman, through literature, who embodied the living metaphor of a boulder,” she explains.

And it was a labour of love, with the author writing three different versions before finding her groove.

“I struggled through the first two novels,” she admits. “Two-and-a-half years of non-stop writing. I tried to create a character to be the hand that shapes the soul and maps out a story for the body.

“I need to want to be with my characters, to see them every day, to be in their company when I re-read the novel, to love them through language, which is the only way of coming into contact with them. But I couldn’t.”

‘Motherhood is not a double-sided coin, it’s more complex, polyphonic, and, like all relationships, it is alive, in motion’

The “light bulb moment” that spurred Baltasar on for her third and final effort came when she let the characters reveal themselves.

“I reached for an image that would spark the third Boulder,” she says, “and what came to me was a memory: 20-year-old me boarding a freighter on Chiloé island [in Chile] on a stormy night.

“I found the voice for the third Boulder, the definitive one, while writing that memory. For six months, the voice tugged me along. It was my compass, and I could have followed it with a blindfold over my eyes.

“I put all my strength and will at the service of language, so that language would be the thing that shaped Boulder. I didn’t know where I was going. The novel ferried us both like a ship to its final destination, and it was there, in that foreign land, that I realised I was in love.”

It was through this revolutionary voyage that she found her two protagonists, Samsa and Boulder, who she describes as “mirror images” of herself.

She travelled to their “darkest, most uncomfortable corners” and in turn found her own darker parts. “Parts that I often repressed and, at times, denied wholesale,” she reveals.

Pieced together through imagination, Baltasar sees her own relationship in Samsa and Boulder’s, soaked in “miscommunication, sexuality, motherhood, desire and solitude.”

For Baltasar, it makes sense, if “humans are polyhedral and infinite” because then we can see ourselves in anyone.

Given the unique topic, Baltasar went on her own journey of discovery.

“I discovered that I contained both a Boulder and a Samsa,” she says, “because motherhood is not a double-sided coin. It’s more complex, polyphonic, and, like all relationships, it is alive, in motion”.

And this portrayal is not without its shades of “light and darkness”, reflecting the challenges contemporary women face and “how intense and interesting life can be when you make the choice to live on the edge”.

The International Booker Prize shortlist will be announced on 18 April.