How a feminist, lesbian music collective powerfully defended trans rights in 1970s Los Angeles

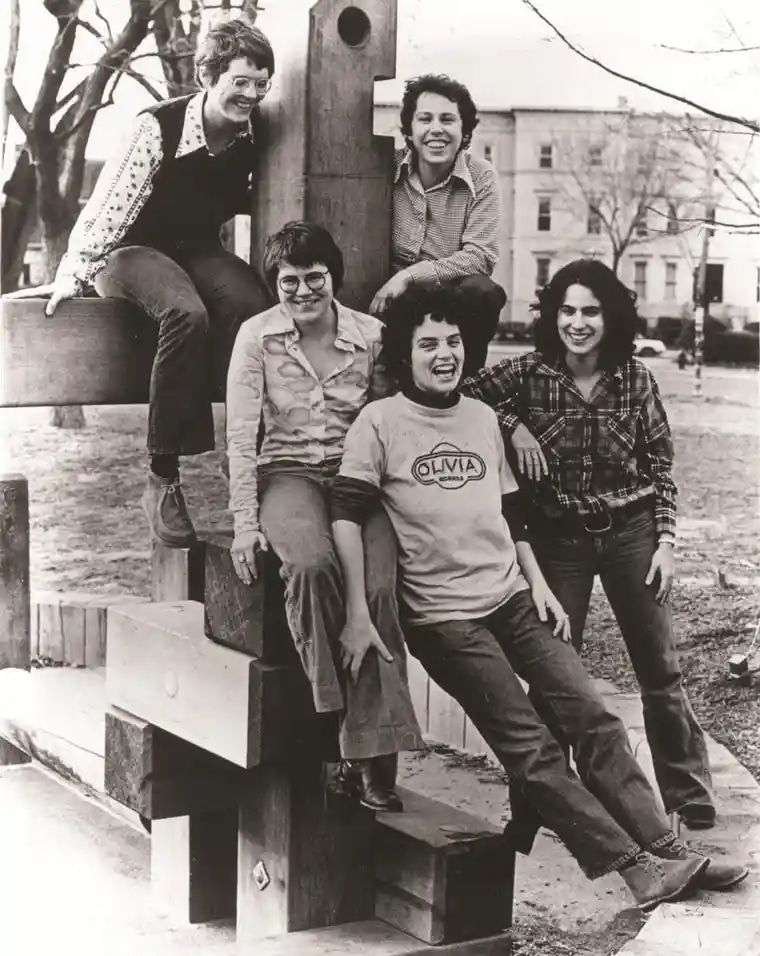

Sandy Stone was welcomed to Olivia Music. (Supplied)

Casual onlookers to the UK media’s ongoing debate about trans people could be forgiven for assuming that cisgender women and trans people are, and have always been, in conflict.

But this assumption erases decades of feminist history.

Trans women were involved in the feminist movement half a century ago, and while some cisgender women objected to their presence, others embraced them. In 1970s Los Angeles, lesbian-feminist women’s music label Olivia Records welcomed a trans woman, Sandy Stone, into their collective as a sound engineer, forming loving relationships that endure to this day.

In the autumn of 1978, Olivia Records produced a concert in Seattle as part of their Varied Voices of Black Women tour. But unlike previous tours, it was – as Stone later put it: “Probably the only women’s music tour that was ever done with serious muscle security.”

Prior to the tour, Olivia had received a tip-off about a lesbian-separatist group called the Gorgons. The Gorgons wore camouflage, carried live weapons, and had threatened to kill Stone if she came to Seattle. Then as now, some feminists virulently opposed the inclusion of trans women like Stone in women’s spaces.

Stone’s relationship with the Olivia collective began in 1974 when it was badly in need of a sound engineer. The strictly women-only collective approached other female engineers and was pointed towards Stone, who had worked with Jimi Hendrix before her transition.

“We all just kind of shrugged our shoulders. And then I said, ‘I gotta go to the grocery store’,” Ginny Berson, one of the founders of Olivia Records, tells PinkNews, of the moment she found out Stone was trans.

The collective did seriously discuss whether it could work with someone who was trans, but it was decided Stone’s commitment to Olivia was more important than her history.

“This is a person who has incredible credentials as a recording engineer, had all the privileges of white men in this society, access to everybody in the world of rock and roll, and was willing to give it up and come work with us, with musicians that nobody had ever heard of before, for hardly any money, to live and work collectively. That’s what mattered to us,” says Berson.

The women of Olivia were no mere co-workers; they lived together in shared houses in the Wilshire district of LA, and no men were allowed to enter. They were all happy to share this rigidly women-only space with a trans woman.

“Nobody went to work for Olivia, you became a member of the collective,” Stone tells PinkNews.

“And that was mutual. You had to be accepted by everyone in the collective. So everybody in the collective had to say, ‘yeah, we want you here’.”

Neither Stone nor the rest of the collective foresaw any difficulties – and she says her understanding of feminist ideals at the time was to “find a way to include all differences in order to build a large movement”.

The first awareness Stone had that anyone might object to her presence came when radical feminist Janice Raymond sent Olivia a chapter of her dissertation, later published as the book The Transsexual Empire, in which Stone was named. In it she claimed Stone played a “very dominant role” at Olivia – something both Stone and Berson strongly deny.

“Raymond had no way of knowing what actually went on at Olivia Records,” Stone said in a 1995 interview.

“The collective meetings were only open to the collective, and there were no leaks to Janice Raymond. Olivia was always run on a consensus basis.

“I also feel that the idea that I could play a ‘dominant’ role in Olivia is demeaning and insulting to the other members of the collective.”

Stone says writing this said more about Raymond than it did her, or any of the women involved in Olivia.

“What Janice Raymond knew about Olivia would fit in the left hand corner of this fingernail,” says Berson.

Olivia began to receive hate mail and death threats, an experience Berson describes as “ugly, destructive and mean-spirited”.

Despite this onslaught, Stone says, she never felt the people writing letters to Olivia represented the majority of opinions in the women’s community.

“I had huge amounts of support. The transphobes were always in a minority,” she says.

“They made more noise than anyone else. But it was always very clear that a huge majority of women were on my side.”

The women of Olivia believed they could get through to those who were angry. It was in this spirit that, in December 1976, they met with a group of women to discuss their concerns.

They agreed to the meeting, Berson wrote in her book Olivia on the Record, “hoping that we would be able to reason together”.

“We were too naive to recognise that the meeting had already been stacked against us.”

The collective later christened this event “Slimy Sunday”.

The meeting was set to take place on the second floor of Old Wives’ Tales, a feminist bookshop in San Francisco – and they knew early on it wasn’t going to be a calm discussion.

“We discovered right before the meeting that there were going to be people there from out of town, and they were what was referred to as ‘notorious head breakers’,” Berson says.

“They were not part of any community that we knew of, they were there just to make trouble.”

The women from Olivia were outnumbered by other women in the room.

A representative from the other group stood up and, Stone says: “[She] made a long, seemingly dispassionate statement about how everyone knew that transgender people were really men and that they were evil and destructive, and had to be rooted out of the women’s community… in a completely neutral, ‘this is just a fact’ tone of voice.”

This prompted Stone to respond.

“I said the first thing that came into my mind. I said, ‘this is all bullshit’ – and that was the only trigger they needed to start screaming. I had said something that was ‘male’. Only men get to say ‘this is bullshit’.”

“So that was essentially the end of the meeting. The women who had come there to attack us immediately started attacking us, they began screaming, they were standing on tables and chairs and waving their fists. I remember some people whom I had thought were allies, just out of their minds with fury.”

When the initial chaos died down, the women demanded Stone leave the room. The collective objected, but Stone agreed to go in the hope it would facilitate the discussion they had hoped for. This concession proved futile.

In Olivia on the Record, Berson wrote: “It would have been smarter if we had all left at that point. Instead, for the next several hours, we listened to women who considered themselves lesbian feminists rip into us.

“Many of these women were not strangers to us. We had worked with them, got high with them. Every now and then, one of them would pull a chair into the middle of the circle, climb onto it, and scream at us.”

The meeting finally broke up when one of the collective members, Jennifer Woodul, went into the bathroom and became hysterical. Both Berson and Stone say some of the women involved in that meeting have since reached out and apologised.

If the meeting was meant to convince the collective to change their minds about Stone, it had the opposite effect. And in 1977 the collective published a statement in Sister magazine, defending their choice to work with Stone:

‘‘Because Sandy decided to give up completely and permanently her male identity and live as a woman and a lesbian, she is now faced with the same kinds of oppression that other women and lesbians face. She must also cope with the ostracism that all of society imposes on a transsexual.

“As to why we did not immediately bring this issue to the attention of the national women’s community, we have to say that to us, Sandy Stone is a person, not an issue.”

Stone had not told the collective when she joined she was still saving up to have surgery. At the time, she had no reason to think it was a problem. Now she saw that it could be.

“The idea that there might be a person with male parts in the women’s collective was an issue that nobody had ever faced before. And nobody had any idea what to do about it,” she says.

What the collective did about it was to pay for Stone’s surgery, which took place in secret.

“That was an act of great love on Olivia’s part. The fact that the collective made that possible is one of the most important moments of my life,” she says.

Harassment and hate mail continued until the collective heard of the threats made by the Gorgons. Stone had received death threats in the past, but, she says, “this seemed to be a new order of threat”.

That fear was warranted. Gorgons turned up at a Seattle concert, and had weapons confiscated by security. In a 2014 interview, she described how she was “pants-wetting scared” at the event.

Ultimately, Stone decided to leave the collective. Olivia was in a precarious financial position and there were potentially ruinous threats of a boycott.

“I began to realise that the vitriol against us was growing at such a terrible rate that we were simply going to be overwhelmed with hatred if I didn’t leave,” she says.

She returned to Santa Cruz and the women’s community there. Two women called a meeting to question whether she should be allowed into women’s spaces. A vote was held, and of around 50 women in attendance, only the two who had called it voted against Stone.

“This is what I think it comes down to when Raymond says trans people divide women,” Stone said in a 1995 interview.

“The overwhelming majority of the women there felt that I should be considered a member of that community and the very few, very angry separatists felt I shouldn’t.”

The accusation that trans people ‘divide’ women is more prominent today than it was in the 1970s, with headlines now splashed across the pages of major media outlets. Much of this coverage pits the rights of trans people and cisgender women against each other, as though the two groups are naturally, diametrically opposed.

The story of Olivia Records paints a different picture. Half a century ago, a group of committed lesbian-separatists welcomed a trans woman into their midst. They shared their work, lives and homes with her. Stone is still friends with several of the women.

Was she a divisive presence simply by devoting her life to Olivia? Or did the division stem from the people who sent death threats and brought live weapons to a women’s music concert?

It’s no coincidence – agree Stone and Berson – that the US is seeing two concurrent right-wing legislative pushes against reproductive and trans healthcare. Both target groups marginalised because of gender; both concern the right to make informed choices about our bodies.

In the face of these attacks, it is more important than ever that we stand together. To do so is to follow in a tradition of love and solidarity that goes back half a century.