Gay man who moved to Russia in 90s shares brutal truth of Moscow life: ‘Humanity is being crushed’

Paul David Gould. (Supplied)

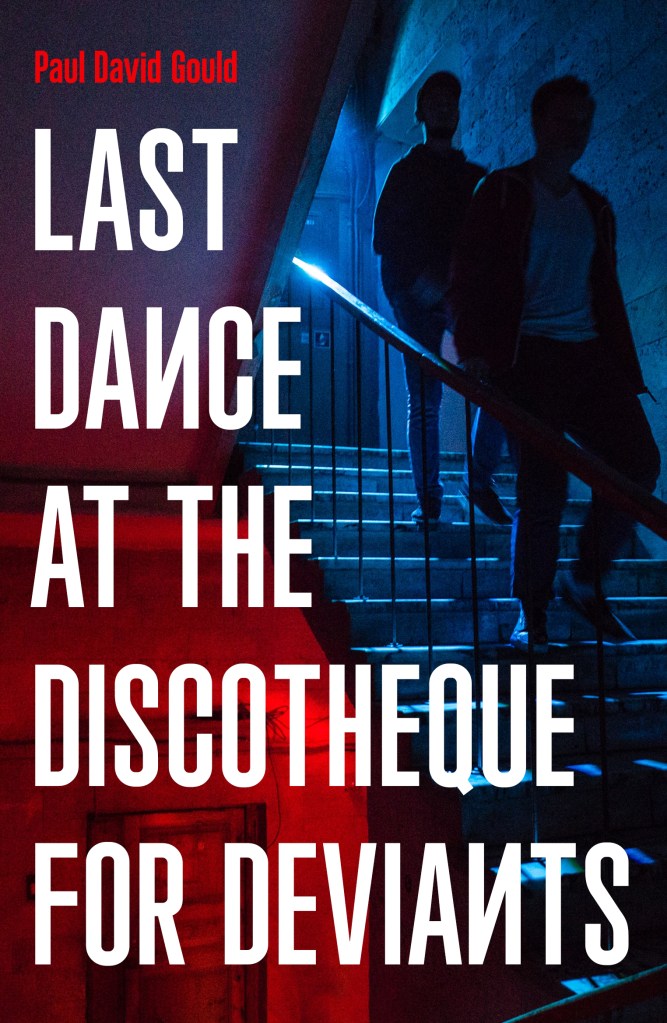

Author Paul David Gould was in his early twenties when he decided to move to Russia – hardly the most welcoming place for a gay, mixed-race man from Huddersfield. Now, in his new novel, Last Dance at the Discotheque for Deviants, he relives the highs and lows of life there.

It’s February 1993, the depths of the freezing Moscow winter. A young Russian man, Dima, hasn’t heard from his boyfriend for three weeks. He could join his roommate, Oleg, and go cruising, but he’s preoccupied by Kostya’s silence. After a few days of unanswered calls, he learns the truth: Kostya is dead.

The rest of Last Dance at the Discotheque for Deviants slowly unravels Kostya’s fate. It’s a gripping mystery, a story of homophobia in all its flavours – violence, rejection, misunderstanding – that shines a light on the broken promise that was early post-Soviet Russia.

In the early 90s, the country was undergoing drastic transformation, opening itself up to the Western world.

“There was a period where it felt more hopeful,” says author and journalist Gould. “When Gorbachev was Soviet leader, he decided to bring down the barriers, open the borders, admit past atrocities, set political prisoners free.

“People were allowed to travel, they started to reduce the nuclear arsenal. By the early 90s, it felt like: hey, Russia is becoming a normal, democratic country with better human rights.”

At the time, Gould was a recent graduate from the University of Birmingham with a degree in Russian and ambitions of becoming a foreign correspondent. He was young, working class, mixed-race and gay. Despite it all, he moved to Russia – first for three months, then for a year-long stint, followed by a more permanent move at the age of 26.

“It’s never been a gay-friendly place, particularly,” he says. “But, of course, there’s more to me or you, or anybody, than just being gay.” At the time, you can imagine there were few places a gay man could travel to and feel truly safe – what was more important to Gould was chasing his dreams.

Homosexuality was decriminalised in Russia in 1993, and Gould found himself on an emerging, but still very much underground, scene, from which his book borrows liberally.

Having first made friends with ex-pats, he soon began attending Discotheques for Sexual Minorities – a series of club nights that changed location regularly, to avoid becoming a target.

“Like it’s described in the book, it was a bit like a school disco,” Gould recalls, “in a canteen with all the tables pushed to the side. You knew everyone, because there was nowhere else [for gay men] to go.

“No one was particularly bothered by being cool. It was just like: here’s somewhere to dance and maybe have a snog. But there was also danger.”

In the book, danger is constant. There’s a violent attack on one of the discotheque nights – which propels the central mystery – as well as violence lurking in cruising spots, at the hands of the police and during sex work. Being gay may have been legalised, but the systematic hunting of queer men wasn’t exactly cracked down upon.

Gould, who today lives in Brighton with his husband, and works as a sub-editor for the Financial Times, was luckier than his characters. He heard about attacks, and had a few lucky escapes, but wasn’t subjected to the kind of violence that befalls some in his book.

There was an incident in 1992, when a gang was waiting outside a party, and he “nearly got beaten up”. Another time, he was out with a Russian boyfriend, and accompanied him to smoke outside.

“Some lads came up to us and I remember hearing this whoosh right next to me, which might have been a baseball bat or something,” he says. “I just got out of the way in time.

“It’s quite a racist society too,” Gould adds. “Once I got on an overnight train and two soldiers walked past me and pushed me against the window. These are guys you don’t mess with, there was nothing I could do about it.”

Gould says it might not have been racism – he’s light-skinned, and knows darker-skinned Black people, African students in particular, had it far worse. Overall, he doesn’t seem too hung up on the violence of the time. More than anything, he’s clearly frustrated by what could have been.

“I, like a lot of journalists and a lot of people observing Russia, felt everything was moving in this positive direction,” he says. “Around 1997 there was even talk of Russia joining NATO or the European Union eventually. From a 2023 perspective, those hopes are in ruins. I deeply despair for Russia.”

Voting is “rigged” for Putin, he says, and it’s clear that the Russian president has no intention of loosening his grip on power. And while many ordinary Russians are afraid of the him and want him out, Gould thinks “a good chunk”, maybe 30 per cent, “really do support him and think he’s strong and he’s sticking it to the west”.

He goes on: “Historically, they’ve had a hankering for what they call a ‘strong leader’. It’s quite scary to think that there are people who are nostalgic for Stalin, who put millions of people in [concentration] camps, who think that Gorbachev was a weakling, which is very sad.”

Ultimately, he says the descent of Russia proves that embracing the West and free market capitalism is no guarantee of human rights.

“It’s a tragic country. It’s a country that has a rich heritage of beautiful classical music and art and history. And yet, there’s this attachment to cruelty and brutality.

“What we’re seeing now under Putin is that they’re starting to attack gay rights again,” he says. “They haven’t criminalised same-sex relations, but they’ve made it a crime to promote them. Even waving a rainbow flag, you can be arrested.

“I think Russia is in danger of becoming a fascist state like Nazi Germany. And LGBT rights are often at the sharp end of that, like the Nazis persecuted LGBT people for no reason other than paranoia and sort of picking a scapegoat.”

What the author wants people to take away from his book is “a sense that Russia is a place where humanity is being crushed by a system… a sense of tragic waste.”

Originally, Gould’s love for Russia grew out of his fascination with its arts.

“I was always into languages at school,” Gould says. “And I think what captured my imagination, when I was about 16, or 17, was I first listened to some classical music, Tchaikovsky, and thought it so beautiful.

“And if you’ve ever seen Swan Lake, particularly that wonderful all-male version a few years ago, you think, well, here’s something wonderful coming from the evil empire. I wanted to know more.”

Certainly, Last Dance at the Discotheque for Deviants continues this legacy in its own way. It may be fiction, but it’s a rare insight into Russia’s LGBTQ+ history. And with the continued crackdown on so-called LGBTQ+ propaganda, authors like Gould, far from Putin’s clutches, are among the few who can safely tell these stories.

Last Dance at the Discotheque for Deviants is published by Unbound.