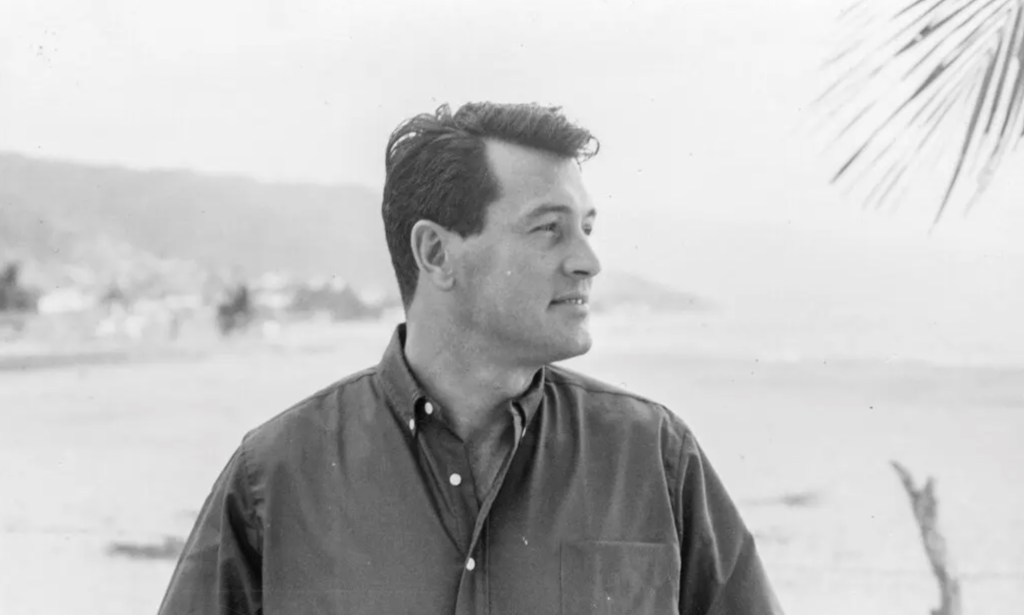

Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed director on ‘horn dog’ star’s secret gay life

Rock Hudson documentary director on uncovering his life as a gay man in Hollywood. (Getty)

Stephen Kijak’s documentary, Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed is a poignant exploration of Rock Hudson’s life as a closeted gay man in Hollywood.

In the late 1940s, Roy Harold Scherer Jr arrived in Los Angeles on the cusp of the golden age of Hollywood, with a dream of making it big. A few years later, he was beloved around the world as screen heartthrob Rock Hudson: Hollywood’s macho, all-American – and seemingly heterosexual – leading man.

On the surface, Hudson had it all. He boasted an adoring fan base, roles in some of the biggest films of the era – such as Giant, for which he landed an Oscar nomination – and was cast as the ideal romantic archetype.

But under the surface, Hudson was leading a vibrant and extraordinary life as a closeted gay man – having several lovers, hosting sex-filled parties and becoming fast friends with the who’s who of queer Hollywood.

Hudson’s former partners include now-retired stockbroker Lee Garlington, actor Marc Christian and Tom Clark (who wrote a memoir about Hudson published in 1990) – not forgetting his sham marriage to Phyllis Gates, the secretary of his agent, Henry Willson, which lasted from 1955 to 1958.

The illusion of Hudson’s picture-perfect life was shattered in 1985 when the public found out he was dying from an AIDS-related illness. As the first high-profile figure to share their diagnosis, he changed the narrative around the disease, at a time when gay men everywhere were facing terrible stigma.

He died in October 1985, aged just 59.

Now, Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed filmmaker Stephen Kijak speaks to PinkNews about retelling Hudson’s story, the state of Hollywood today and Rock’s lasting legacy.

What inspired you to tell Rock Hudson’s story and why did now feel like the right time?

It’s always a good time to tell these stories of our queer elders [but] especially now, when our rights all across the board are being challenged. Definitely in the States, it’s feeling like we’re under pressure again.

Visibility and history are always important and [Rock Hudson] has faded into the past. His cinematic legacy was really obscured by his death in the 80s and the shock and scandal that surrounded it at the time. People don’t remember the positive effects that came in the wake of that.

What are your personal ties to the star? Have you always been fascinated by him as a figure in cinematic history?

I was always a fan of the directors who he would have worked with. I loved John Frankenheimer and obviously the Douglas Sirk canon is deliciously camp, gorgeous and brilliant filmmaking and [Rock] was in many of those films. When the producer came to me with this documentary idea, it was just too good to pass up.

It presented itself at a great moment. [I wanted] to tell more LGBTQ stories and to do films with more of a social point to them.

What was the documentary-making process like?

It was heavily archival, so a lot of it was just research and taking the time to watch 65-plus Rock Hudson movies.

I loved the small self-aware snippets slotted into the documentary taken from Rock Hudson films where he seems to be referring to his sexuality …

Once you make 60 to 70 films and TV shows, there are going to be little bits where almost anybody’s life is reflected somewhere in there. There’s so much to work with and I like appropriation. It was fun rearranging dialogue [from his films] to see how it could reflect his real life.

We’re indebted greatly to a filmmaker named Mark Rapaport, who did a film called Rock Hudson’s Home Movies in the early 90s [which] was essentially just a compilation of all these double entendres and secret queer-coded messages in his films.

I wanted to go broader and bigger, by starting to cut different films to create an alternate universe with a queer narrative where Rock could contemplate gay marriage or flirt with Rod Taylor.

How did you go about choosing the interviewees who gave an insight into Rock’s life?

The choice was made to film only a certain group of men who were in his life. Everyone had to have a very personal, intimate connection with him. I wanted to create a generational portrait of men to take you from pre-Stonewall liberation to the other side of the AIDS crisis. The lost generation, who don’t really get a lot of attention paid to them.

It’s a fascinating slice of history where they have witnessed these two really important crisis points in queer culture.

Did anything you discovered about Rock’s life shock or surprise you?

Nothing shocks or surprises me, to be honest. I mean, you can read more about his wild sex life, he was a total horn dog. Anyone who says differently is full of it because he had a lot of sex and he enjoyed himself. He was a rich, famous, white, privileged person who lived in this bubble. Every person we encountered had nothing bad to say about the man. Just crazy.

But he was also very conservative, politically and socially. They were just a different generation, you know?

Do you think Hollywood and its attitude towards LGBTQ+ people has changed since Rock’s era?

Yes and no. There are out people who have progressed within the industry and have great careers and are real advocates and champions. They are heroes to us all and very brave, for their visibility.

But what actor do you know of who has ascended to those heights who eventually says: ‘Hey, everyone, guess what, I’m gay?’ Ellen DeGeneres did, but I can think of so few who took that kind of a risk. Are there gay men hiding in the upper echelons of fame? Probably.

I know there are a lot of younger up-and-coming actors who are still afraid because it’s still a stigma. Who are the big gay actors who are cast as straight romantic leads or big action heroes? I can’t really think of one. We’ve made some progress but then there are systemic problems that are still rooted in there, that are very hard to fix.

Do you think Rock Hudson would have come out as a gay man of his own accord if he was born now?

He’s such a product of his times, coming out was just not in [that generation’s] DNA. They had nothing to gain by doing it. When it was announced that he had AIDS, that was the pivot. What happened on the other side of that is, almost, despite him. It doesn’t even have anything to do with him any more. It moved this stigma around AIDS into the mainstream in a way that was very much needed at the time.

Here and now, knowing what we know about him, he probably would have just nailed that closet door shut if he was making money and making big movies.

What does it mean to be able to introduce Rock Hudson to a new generation?

It’s very important to me that we remind people what it was like in 1985, in the early days of the AIDS crisis. Because of the advances in medicine, people with HIV are now living healthy, long lives. Now, people tend to forget the horrors of the 80s and the 90s.

It’s a reminder of where we were, and where we could go again, especially when politically and socially things are sliding back to the right. Real antagonism towards LGBTQ+ people is back in fashion. What’s really rewarding and also slightly heart-breaking is speaking to people who did live through it.

What has been the wider reaction to the film so far?

It’s been very moving for people who lived through that time and lost people close to them. They were totally shattered, weeping and having to leave the theatre.

The only negative thing is the people who are so freaked out that gay men have sex. They hear about Rock’s endowments or the friend he had a fling with, and they become prudish and paranoid, and think the movie is only about sex and gossip. That’s really missing the point – this is our attempt to keep his legacy alive.

Rock Hudson: All The Heaven Allowed will be available on digital platforms from 23 October.

To learn more about HIV and AIDS research, testing and treatment, visit amFAR or the Terrence Higgins Trust.