Conner Habib is redefining intimacy in menacing queer horror novel ‘Hawk Mountain’

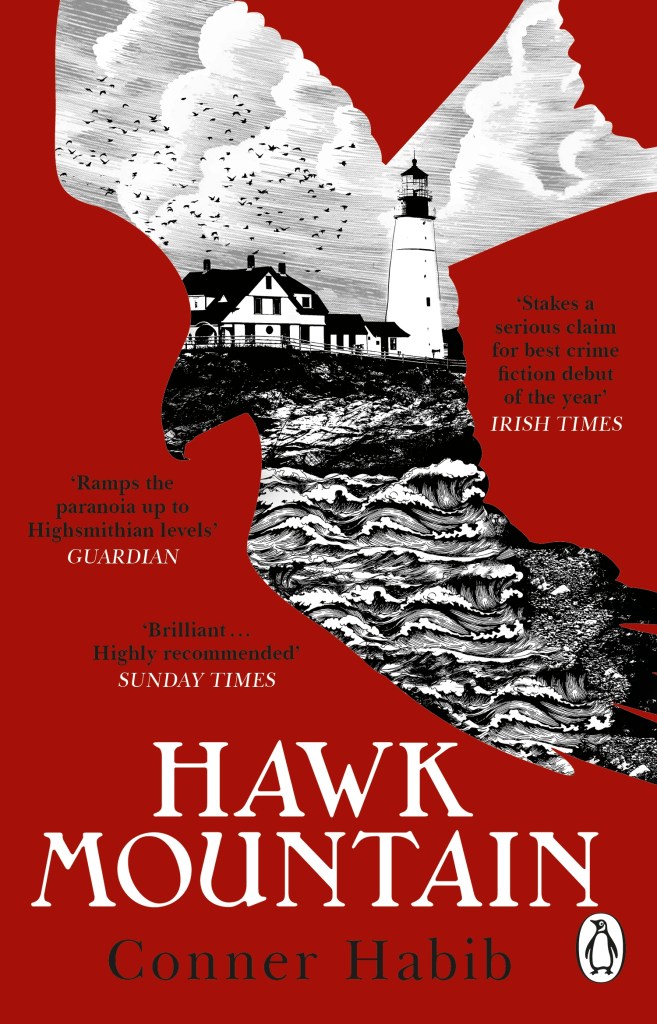

Author Conner Habib’s debut novel Hawk Mountain is creepy, bloody, quietly queer thriller. (AI Higgins/supplied)

Author Conner Habib never intended to write a horror story. He’d always wanted to write a book of some description (he’s been writing since he was seven years old), and his debut, PEN/Faulkner Award long-listed novel Hawk Mountain started out as something that was almost comically over-the-top.

Writer, Against Everyone podcast host and former porn star Habib began writing what would become Hawk Mountain 16 years ago, while studying at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the US.

“It was much different. It was super melodramatic [and] over the top because I was really interested in how murder and crime and violence are actually very melodramatic in their own way – these really big gestures that teach us something about ourselves,” he tells PinkNews.

His fellow students, and his teacher, were not impressed. “It didn’t really work,” laughs the author, who is of Syrian and Irish American descent, but who lives in Dublin.

“In fact, my classmates hated it. One of [them] said: ‘You disgust me’. But I kept thinking about the characters. So, they just lingered and lingered until I was ready to write it as a book.”

After a “freeing” conversation with Folk of the Air series author Holly Black, Habib realised that he was capable of – and indeed was – writing a horror story.

Hawk Mountain is in equal parts chilling and thrilling. It follows school teacher and single father Todd Nasca, who, while on the beach with his young son Anthony, has a chance encounter with former high school bully and quiet crush, Jack Gates.

Jack is surprisingly elated to see him and, caught off guard by the unexpected reunion, Todd agrees to a catch-up. That turns into staying the night, and staying the night turns into Jack attempting to infiltrate all areas of Todd and Anthony’s home life.

Soon enough, there’s a body to deal with.

Now, Habib opens up to PinkNews about the LGBTQ+ community’s connection to horror, why he didn’t want Hawk Mountain billed as a queer novel, and how the book changes the way we look at intimacy.

Hawk Mountain started as a melodramatic, shorter story 16 years ago. How did it become what it is today?

There’s still a sort of melodrama feel to it, but in a different way. I’m very into [The Talented Mr Ripley author] Patricia Highsmith, and that would be the person who most people compare the book to, which is a tremendous compliment to me.

I was talking to author Holly Black and I was describing the book to her and she said: “Oh, you’re writing a horror novel.” When she said that, it felt very freeing, because if you think of what you’re doing as horror, the parameters and limits on what’s available to you completely change.

It’s something I think people really like about horror. It doesn’t obey any rule, whether it’s the laws of physics and what the normal world looks like to us, or it’s just the rules of what we consider civil and decent.

Non-binary author Andrea Lawlor said that Hawk Mountain is “a story that knows cis, hetero, patriarchy is the villain,” because there are definitely some hints that Jack and Todd have both struggled with masculinity and sexuality. Was that intentional?

I didn’t set out to do anything like that. There was a lot of talk about, ‘should we say this is a queer horror novel? Should we say that this is about toxic masculinity?’ I had to keep saying: ‘No, I don’t want you to say any of that.’ Not because it’s not there, but because I want people to find their way in as individuals encountering the novel.

There are only really two blatantly queer characters in the book that just say it. [For] everybody else, it’s a bit ambiguous about where they might locate their sexuality throughout their lives. I wanted people to be able to resonate with that on whatever level they want.

If they resonate with the one Arab queer character, that’s great [or] if they resonate with a person wrestling with their sexuality, or a kid being bullied by adults or other kids. There are so many pathways in.

Of course, being Arab and gay, and a former sex worker myself, all those things are really important to me and who I am, but I don’t try to write them in. They just radiate out of my own being into the work.

While there are hints of queer intimacy throughout the book, it takes a while until there is any physical, explicit intimacy between characters. Did you want people to just be able to make their own assumptions?

There are lots of moments of intimacy before then, it’s just that what we consider intimacy is quite narrow. I think antagonisms and even aggression can be instances of intimacy between people – it’s just not good intimacy.

The relationship, for instance, that I had with the people who bullied me in high school, those people are burned into my mind, they live in me. So, is that intimacy?

On that note, this is a story about love, hate, bullying, obsession, terror. Are any of your experiences reflected in the characters of Todd or Jack?

Very few of the actual experiences were experiences of mine, but there are plenty of bullying experiences that were adjacent to them. I definitely suffered plenty of bullying and, like Todd, it wasn’t because I had definitively come out of the closet or anything. I wasn’t [out] in high school. The bullies knew something about me that I hadn’t even said.

I don’t think I was a very nice person as a result of that, either. I was probably a total arsehole to people who probably deserved me to be kinder to them. When people are cruel to you, threatening you, you look for ways to seize power, because it’s all been taken away from you. The trick is to walk away from the power struggle completely.

Horror is a genre that members of the LGBTQ+ community have always been drawn to, from Dracula to M3GAN. Why do you think that is?

A lot of us live lives of concealment and outsiderness. It’s like we experience a secret intimacy with the world. Our thoughts feel threatening and dangerous to us, then the rest of the world, and how people respond to us feels threatening and dangerous.

We play out all these fantasies that we feel must be hidden away, that can only really exist in our heads and are even frightening to us in our heads. Even as there’s been some shifting landscape with what’s repressed and what’s spoken out loud, there’s always still that feeling of difference.

Horror offers spirituality to people, which might sound surprising, but I think especially for LGBTQ+ people – who feel often ostracised and alienated from spiritual life – encountering things that have a religious tone, a spiritual tone, the supernatural, the otherworldly, the things that rupture our view of reality, gives us access to that.

Hawk Mountain is out now.